Webinar Recap: Donor Research Findings

July 14, 2021

(Video replay at end of article)

Advisory Board for the Arts recently completed a massive research initiative around donor motivations and behavior, with over 5,000 surveys completed by current and former donors to arts organizations from the US, UK and Canada.

The challenge: during the pandemic, our reliance on very large donors increased, accelerating a decades-long trend. As we transition to the ‘new normal,’ our financial health depends on accelerating contribution growth from deeper within the donor pool.

In this week’s ABA Live! webinar, we reviewed the high-level findings from this research study, the assumptions supported and refuted by the data, and the implications of our findings for arts organizations in this moment.

The Current Challenge and Opportunity

We began our meeting by painting a picture of the current landscape of arts philanthropy.

While it has certainly been a difficult past year and half for development teams, not all of our challenges in the donor space are due to the pandemic — there have been very real trends in recent years that give us some reason to worry. Primarily, we see that donations are trending upwards but from a smaller group of donors, creating a concentration of risk at the top. This stands true across the board, as even with differences in the culture of giving in Europe, the endpoint is the same: fewer donors giving more money.

Of course, the difficulties arts organizations faced during the pandemic were significant, including an even higher reliance on the individual donor in absence of regular ticket sales, foundation grants, and government support. While the number of these individual donors actually increased by 15% (due to ticket donations, crisis support funds, and more), the dollar amount of donations went down.

So, we now face a pivotal moment. On one hand, the disruption of COVID-19 is worrisome, with donors experiencing fatigue, donations to other causes turning funds away from the arts, and newer generations being less engaged with our industry — while at the same time being on the cusp of a massive wealth transfer.

On the other hand, this moment of widespread change is a real opportunity for innovation in the fundraising space. We need to think about what we can change, the challenges we face and the assumptions we make behind those challenges — by testing those assumptions, we can find new, sustainable ways to operate.

The below model is based on interviews we conducted with development leaders at over 55 arts organizations across the world:

As pictured above, we typically think of our current fundraising activities as falling into a classic “donor pyramid.” You can see the actions we then take just to the right of those levels.

Based on this approach and associated challenges we heard on our calls, we pulled out three main assumptions that we tend to to make about our donors:

We assume that transactional benefits appeal to most of our low-end donors, which is why they stay and why they increase.

We assume that mid-tier donors naturally shift to be more philanthropic, as the value of their donation increases relative to the benefit they receive, and we want to figure out how to speed up this process.

We cultivate our top donors based on their deep love and appreciation for the art form.

So in testing these assumptions we developed our research question: how can we resonate more deeply with new, high potential donors and move them from transactional to philanthropic, to accelerate their velocity to major giving?

Results of Quantitative Analysis

Starting at the end of 2020, we recruited over 5,000 donors to fill out our extensive survey, from 47 different organizations both in and out of our membership of arts organizations. Our respondents donated at least $250 once in the past three years, but also went up to the major donor level.

Our analysis process was then divided into three parts:

Question clustering: this analysis shows where different questions actually reflect the same concept.

Cluster analysis: we then slotted donors into different segments mathematically, and looked at the different behavior of different segments using cross-tabs against other survey questions.

Regression analysis: finally, we looked at which elements drive higher donation levels, at different tiers of donation.

Through these various analyses, we are able to control for location, to identify items that applied both during and beyond the pandemic period, and also to understand patterns -- specifically, in order to go beyond what donors said to understand what else that means.

First, we discussed our cluster analysis, in which we grouped donors into groups that share motivations in their giving. What we found was a bit surprising: donors clustered into just three motivations. The groups were as follows:

Benefits Donors: these individuals are motivated by accessing benefits, accessing the network of other donors, and the potential tax write-off of giving.

Arts Lovers: these are people who are motivated primarily by the love of the art and by the desire to support the cultural vibrancy of their area.

Community Donors: the motivation of these donors is twofold: one is that they support projects and community activities — these are the people who want to have impact on the community where they live. The other is that they support friends and family and access the network of donors — they want to be part of a community.

Another surprise is that each of these donor segments represents about one-third of our donor base -- that is, our donors are spread fairly evenly across motivations. And unlike we had assumed, donors did not start transactional and become more philanthropic as they moved up towards major gift giving. In fact, it was almost the opposite:

In the graph above, we see that both Benefits donors and Community donors pick up steam into higher donor tiers. Arts lovers, on the other hand, decline as a percentage of the whole.

To get a fuller picture, we looked at each donor type a bit more closely.

Benefits Donors

From our data, it is clear that many donors place a high value on our benefits, so offering them is certainly an important element of our fundraising efforts. It is, however, important to note that benefits-driven donors are least likely to increase their giving, as they get more easily locked into levels. We looked at who increased their donation between 2018 and 2020 and it was only 26% of benefits donors — lower than any other segment.

Arts Lovers

One clue for why these donors are such a large group at the lower end of giving comes from the regression analysis we did on donors who gave below $1000. The most important driver of donation at that level is emotional connection to the organization, which we see as tightly connected to loving and understanding the art form.

Why do these donors not give as much at the higher levels? One potential indicator is that arts lovers tend to donate more to other nonprofits, particularly environmental and social justice nonprofits. They love the arts, but it seems they also love to change the world. It may then be harder to be one of their top priorities.

Community Donors

These donors are 35% of the top-end donors, and they are surprisingly engaged with your organization, in roles like board members or volunteers — in fact, nearly half of the surveyed donors who shared that they were on the board or a committee fell into this category. They are also most likely to attend your events, as well as being active in the greater community.

The most interesting point about community donors, however, is their giving habit. We looked at average donation size across our survey participants, separated by annual giving and “other” giving (galas, campaigns, and anything the donor themselves didn’t consider annual giving).

While the three groups had similar levels of annual giving, the community donor gave twice as much to “other” giving. When you add up the total giving across three years, the community donor gives the most.

In short, your community-centric donors have an extremely high potential to help increase both your funding and number of donors.

Now, the power of community-motivated donors is not a brand new idea. A past Washington Post article we read points out that younger philanthropists tend to donate to community development, and that when they are donating to the arts, they give to places with strong education and community development. As Bob Lynch, formerly of Americans for the Arts, put it: your organization has to offer “Arts and Something Else.”

It’s not that newer generations don’t appreciate the arts, just that these donors need to understand what the art is doing for them and to progress the interests of the community. Fortunately, there are many versions of “and something else” that we can offer by asking ourselves what the nature is of the progress or change that we are trying to make in the community that we are using our art form as a vehicle to effect. And the data tell us there’s a large, generous, set of people interested in being part of the “something else” we provide.

Implications of the Findings

For the final portion of our webinar, we looked at what it might mean to embrace a community-centric fundraising approach. This involves a real mindset shifts for arts organizations who want to truly embrace this notion of creating community value:

Every arts organization has something unique that they bring to their community — and are part of unique communities — so we turned it over to our attendees to learn what a “community donor” means to them. Here are some of the great responses we heard:

Impact

Restorative justice

Sense of belonging

Shared experience and growth

Spiritual wellness

Understanding who they help

Upholding a legacy

Community revitalization

Connection

Contributing to social progress

Empathy

Equity

Escaping from the mundane

Helping to solve a problem

In our interviews, we heard generally three types of a Community donor described:

Standing: this kind of Community donor wants the area where they live to have a reputation as a place where arts and culture are available for all. They position themselves as a pillar of society.

Belonging: for these donors, community is about belonging to something bigger than themselves.

Change: finally, these are the change agents, donors looking to be part of a movement. The emotional intensity of a movement is likely to attract strong advocates, even as it may risk the commitment of some current audiences and donors if we take a strong stance.

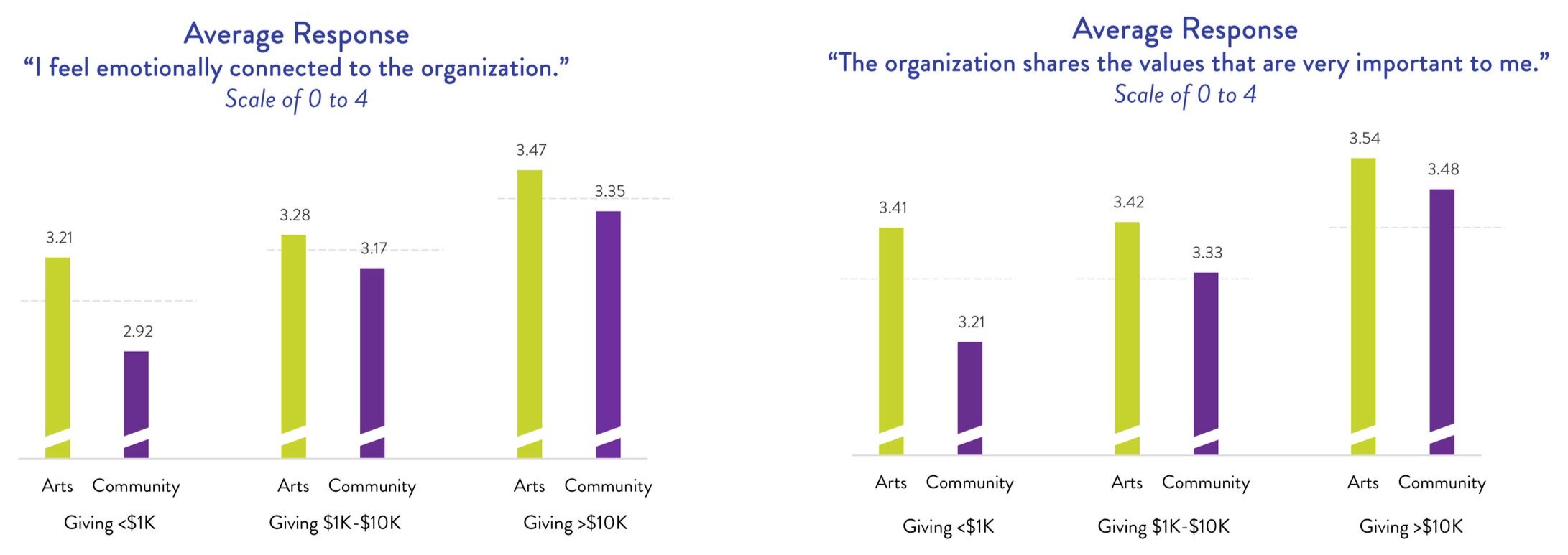

In our study, we found evidence for a move towards that “Change” donor. When we look at how emotionally connected the two philanthropic donor types are to the organization — the arts lovers and community donors — the community donors are consistently less connected. You can see that in the left hand chart below. On the right you can see that they also are less likely to believe the organization shares their values.

Two other sources of data further emphasize this point.

In the recent Culture Track survey run by LaPlaca Cohen and Slover Linett, we saw that our non-white community members most want community and belonging from their arts and culture organizations — even more than great content, whether entertaining or reflective.

And in a generational study by Colleen Dilenschneider of Know Your Own Bone, we saw how Millennials are much more likely to say that they wanted to join or be part OF something. They also said that they were interested in supporting the mission of their chosen organization. These are both in contrast to being asked for a donation, which is a big part of the current relationship-based approach to fundraising.

So what we see is that the meaning of community will evolve. Below, we have charted the three different types of community we defined, along with their likely proportions over time.

The conclusion we can all draw from this is twofold. First, our purpose needs to be a guidepost for everything we do. We send signals with every communication and every activity, and those signals add up to us living our purpose as an organization.

Second, that purpose needs to be at a higher level than making great art, to attract and retain audiences and philanthropic donors who are not connoisseurs. It must be about the arts and something else — what the art accomplishes for our patrons and for the world.

At ABA, we refer to this “something else” as “shared values.” A shared value is a belief that both our organization and our customers have about a higher purpose, passion, or philosophy that has meaning in our lives beyond our specific genre or the arts in general. What a shared value does is connect the core belief of the people in the organization with the human values of the people the organization serves.

Below, we’ve built out a framework of how an arts organization might orient their activities around the shared value of “empathy” — including things to avoid in order to stay true to this purpose:

So where do we go from here? As a first step, we took our mental model of the donor pyramid and updated it to reflect the new knowledge we have gained from our research. The updated mental model has values at its center, values that are manifested both in the art and the organization’s engagement with its donors and community:

Over time, individuals attracted by the good these values create in the community are drawn toward the center. And the model provides us some useful questions for reflection. If we were trying to pull people toward these shared values:

What conversations would we want to host and who should be invited?

How would we reinforce belonging and create opportunities for deeper engagement?

How can we demonstrate our commitment to the community through unified programs and partnerships?

For many of us, this vision may be a long way off. But the right time to start is now. The sooner we start, the more credibility we’ll have that we are really about the shared values we espouse.

For further insight on the connections between shared values and your community, check out our latest article, Using Your Purpose To Build Community Engagement.